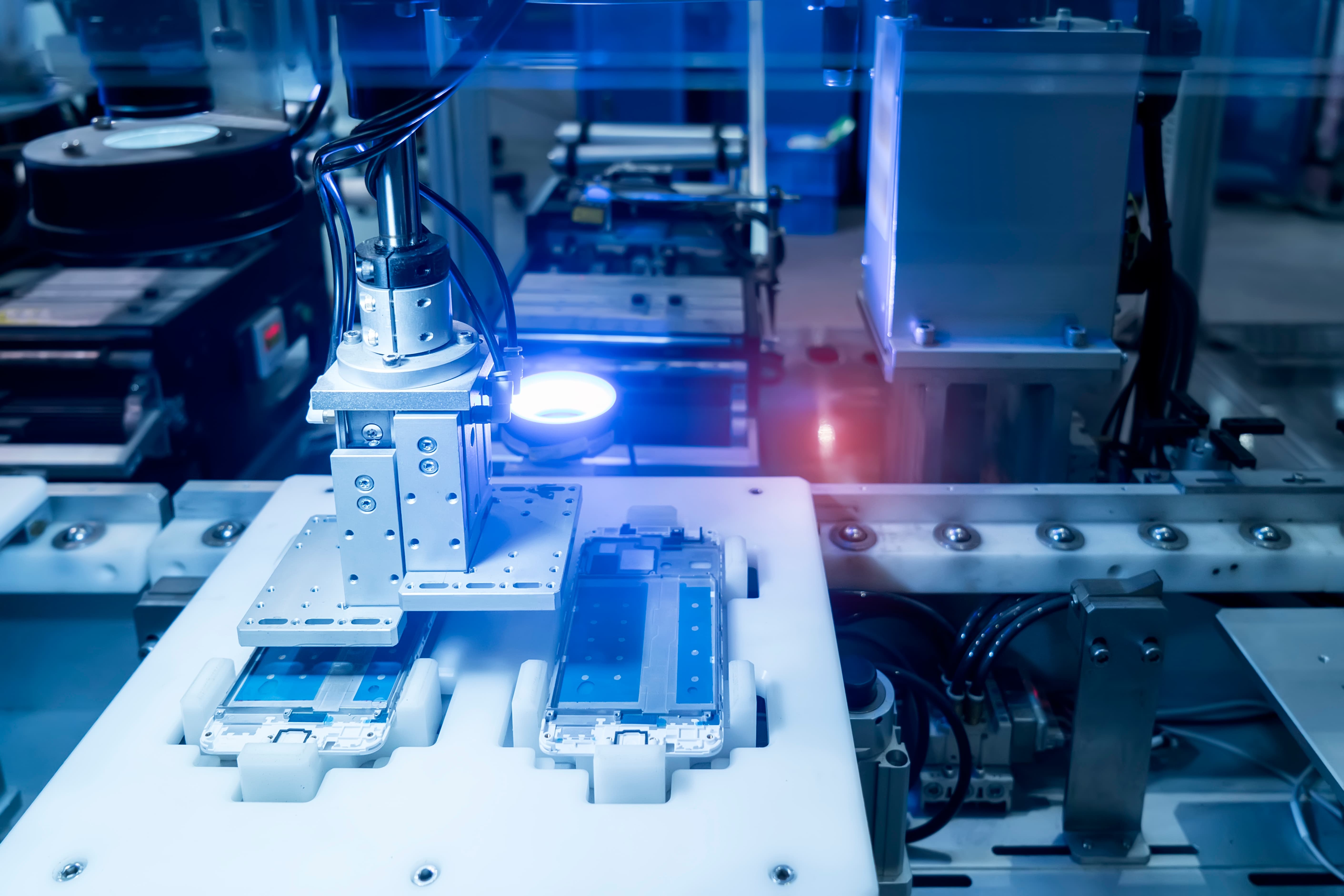

In fields such as industrial automation, intelligent manufacturing, new energy, and automotive electronics, pressure is the most fundamental core detection parameter. As the key sensing component that converts pressure into electrical signals, pressure sensors act as the tactile nerves of various measurement and control systems. Their performance directly determines the accuracy, stability, and scenario adaptability of detection systems. From on-site monitoring in traditional industries to micro-pressure detection in consumer electronics and extreme environment sensing in high-end equipment, the application boundaries of pressure sensors continue to expand.

With breakthroughs in materials science and MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) technology, pressure sensors have evolved from early mechanical components to integrated, miniaturized, and intelligent chips, with their core technologies undergoing constant iteration. This article dissects the mainstream sensing principles, sorts out the evolution of technologies, and clarifies the technological development and industrial application logic of pressure sensors.

I. Four Core Sensing Principles: Each Excels in Adapting to Different Scenarios

The core logic of pressure sensors is to utilize the physical deformation effect of sensitive elements to convert pressure signals (such as gauge pressure, absolute pressure, and differential pressure) into quantifiable electrical signals (such as resistance, capacitance, and voltage). The principles and materials of sensitive elements determine the core performance of sensors. At present, there are four mainstream technical routes in industrial and civil fields, forming differentiated and complementary solutions that cover most detection scenarios.

1. Piezoresistive: The Preferred Choice for Mainstream Industry with High Precision and Integration

Based on the piezoresistive effect of semiconductor monocrystalline silicon, the lattice of silicon material deforms under pressure, leading to a change in resistivity, which is converted into a linear voltage signal through a Wheatstone bridge.Core advantages: High precision (0.05% FS ~ 0.1% FS), fast response (microsecond level), small size, capable of measuring full-range pressure, and excellent stability after temperature compensation.Typical applications: Mainstream scenarios such as industrial automation, new energy lithium batteries, hydraulics and pneumatics, and automotive electronics.

2. Capacitive: Strong Anti-Interference, Adapted to Harsh Environments

Utilizing the parallel plate capacitance effect, pressure drives the deformation of an elastic movable electrode plate, changing the plate spacing/area, and the pressure signal is converted from the capacitance variation.Core advantages: Good temperature stability, strong anti-electromagnetic interference, wide measurement range (from high vacuum to ultra-high pressure), no mechanical wear, and long service life.Typical applications: Harsh working conditions with strong corrosion and vibration such as chemical industry, metallurgy, water treatment, and petroleum and natural gas.

3. Piezoelectric: A Specialist in Dynamic Pressure with Accurate Transient Detection

Based on the direct piezoelectric effect of piezoelectric materials, pressure deformation causes quartz crystals/piezoelectric ceramics to generate polarized charges, which are converted into voltage signals through a charge amplifier.Core advantages: Ultimate dynamic response (nanosecond level), no zero drift, and accurate capture of transient pressure changes such as impact, pulsation, and explosion.Shortcomings: Unable to detect static pressure and requires a dedicated charge amplifier.Typical applications: High-end scenarios such as aerospace, automotive crash testing, industrial blasting, and fluid dynamic detection.

4. Strain Gauge: Classic and Mature, Low-Cost and Widely Adaptable

Utilizing the strain effect of metal materials, pressure drives the deformation of metal strain gauges, changing the resistance value and converting it into an electrical signal through a bridge circuit.Core advantages: Simple process, low cost, wide measurement range (from low pressure to ultra-high pressure), and strong environmental adaptability.Shortcomings: Slightly lower precision (0.1% FS ~ 0.5% FS) and slow response speed.Typical applications: Scenarios with low precision requirements such as engineering machinery, metallurgical mining, and traditional manufacturing.In addition, special pressure sensors such as resonant, optical, and MCS (Multi-Metal Cladding System) types feature high precision (0.01% FS ~ 0.05% FS) and outstanding anti-interference and extreme environment resistance capabilities, which are mainly applied in high-end precision detection scenarios such as aerospace, precision metrology, and nuclear industry.

II. Four Generations of Technological Iteration: From Discrete Components to MEMS Intelligent Integrated Chips

The development of pressure sensors epitomizes the coordinated progress of materials science and microelectronic processes, always centering on the core direction of higher precision, smaller size, faster response, stronger adaptability, and lower cost. It has undergone four key upgrades, realizing a leap from "basic detection" to "core of intelligent sensing", and its application scenarios have extended from industrial-specific to diverse civil fields.

1st Generation: Mechanical Detection Components (No Electrical Signal Conversion)

With Bourdon tubes and diaphragms as the core, they rely on mechanical deformation to drive pointer display, only enabling on-site manual reading with low precision and no remote transmission capability. At present, they are only used as auxiliary detection methods in traditional scenarios.

2nd Generation: Traditional Electronic Sensors (Discrete Component Structure)

Realizing the first conversion of pressure to electrical signals, strain gauge and piezoelectric types became mainstream. However, the sensitive elements and conditioning circuits were independent from each other, featuring large size, low precision, poor temperature stability, and the need for dedicated circuit adaptation, which were only applied in early simple industrial detection.

3rd Generation: Integrated Pressure Sensors (Chip-Level Process Upgrade)

Microelectronic processes promoted the chip-level integration of sensitive elements and conditioning circuits, with diffused silicon and ceramic capacitive sensors becoming mainstream. Temperature/nonlinear compensation was added, and the precision was raised to over 0.1% FS. Industrial-grade packaging achieved waterproof and corrosion-resistant performance, driving the large-scale popularization of pressure sensors in industries such as chemical engineering and electric power.

4th Generation: MEMS Pressure Sensors (Miniaturization, Integration, Intelligence)

MEMS technology has become the core driving force. Through semiconductor microfabrication processes, the monolithic integration of sensitive elements, compensation circuits, and amplifier circuits on a single silicon wafer is realized, with the size reduced to the millimeter level and the precision maintained at over 0.05% FS. Mass production has also greatly reduced costs. The new generation of MEMS sensors has achieved multi-functional integration (pressure + temperature detection, AD conversion) and low-power intelligence (integrated MCU and wireless communication modules), expanding pressure sensors from industrial components to civil fields such as smartphones, tire pressure monitoring, medical sphygmomanometers, and the Internet of Things (IoT). At present, they account for more than 70% of the global market share and have become the industry mainstream.

III. Three Core Driving Forces for Technological Iteration

The upgrading of pressure sensors is not an isolated innovation, but is jointly driven by market demand, materials science, and core processes, forming a positive cycle of demand driving technology and technology empowering demand, which promotes the continuous breakthrough of their performance boundaries.

1. Market Demand: Differentiated and High-End Demands in Various Industries Point Out the Direction

Industrial automation requires high precision and anti-interference; new energy demands explosion-proof and corrosion-resistant performance; consumer electronics calls for miniaturization and low cost; aerospace requires adaptation to extreme temperature ranges and high reliability. Diverse demands drive the continuous enrichment of technical routes.

2. Materials Science: Material Innovation is the Foundation for Performance Improvement

Monocrystalline silicon drives the integration of piezoresistive sensors; piezoelectric ceramics enhance dynamic detection performance; titanium alloy/Hastelloy improve corrosion resistance; third-generation semiconductors (silicon carbide, gallium nitride) adapt to extreme temperature ranges. Material breakthroughs continue to raise the upper limit of performance.

3. Core Processes: Microelectronics and Precision Manufacturing Realize Integration and Miniaturization

MEMS microfabrication processes enable monolithic integration; semiconductor packaging processes improve environmental adaptability; high-precision detection chips solve the problem of weak signal capture. Technological progress realizes the synchronous development of performance improvement, size reduction, and cost reduction.

IV. Future Development Trends: Ultimate Performance + Intelligent Integration + Scenario Customization

Driven by the rapid development of Industry 4.0, the Internet of Things (IoT) and new energy, as well as breakthroughs in third-generation semiconductors, flexible electronics and artificial intelligence technologies, pressure sensors will continue to advance toward extreme environment adaptability, high integration, low-power wireless connectivity and scenario-specific customization. They are evolving from single pressure detection to multi-parameter fusion sensing, emerging as core nodes in intelligent measurement and control systems.

1. Upgraded Adaptability to Extreme Environments

Leveraging third-generation semiconductors such as silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN), pressure sensors will achieve adaptation to an ultra-wide temperature range of -200℃ to 800℃, ultra-high pressure and intense radiation. This will expand their application boundaries in high-end fields including aerospace, deep-sea exploration and semiconductor manufacturing.

2. In-Depth Advancement of MEMS Technology

MEMS technology will enable the integrated integration of sensing + processing + transmission + power supply. Single chips will integrate multi-parameter detection (e.g., pressure, temperature and humidity) to become composite sensing chips. Meanwhile, low-power manufacturing processes will be optimized to adapt to wireless IoT sensing networks.

3. Integration of Wireless Connectivity and Intelligence

By integrating wireless modules such as LoRa, NB-IoT and Bluetooth, and combining with edge computing technology, pressure sensors will realize remote pressure data collection, real-time analysis, fault self-diagnosis and trend prediction. Transforming into intelligent IoT sensing nodes, they will provide data support for predictive equipment maintenance and process optimization.

4. Scenario-Specific Customization as the Mainstream

General-purpose products will be gradually replaced by customized solutions. Targeting niche scenarios such as lithium batteries, hydrogen energy, smart water utilities and medical equipment, specialized sensors with explosion-proof, low-power and miniaturized features will be developed. We will provide customized design + integrated solutions to achieve in-depth alignment between technology and application scenarios.

5. Rapid Development of Flexible Pressure Sensors

Based on flexible piezoelectric films and strain materials, flexible pressure sensors will feature bendable and stretchable properties. They will adapt to unconventional detection scenarios such as irregular surfaces, human skin and intelligent robots, expanding into emerging fields including wearable devices, smart apparel and human-computer interaction.

V. Conclusion

The development of pressure sensors is a technological evolution from mechanical deformation sensing to electrical signal conversion, and further to MEMS intelligent integration. The four core sensing principles have laid the technical foundation of the industry, while four generations of technological iteration have driven pressure sensors to evolve from discrete components to miniaturized chips, and from industrial-specific devices to widely adopted civil products.

Driven by the synergy of market demand, materials science and core manufacturing processes, pressure sensors have become the core sensing foundation for industrial automation, intelligent manufacturing and the IoT, with applications spanning diverse fields including industry, consumer electronics, medical care and aerospace. In the future, with the integrated application of various new technologies, pressure sensors will evolve beyond mere detection devices to become composite sensing nodes with intelligent analysis and multi-parameter fusion capabilities. They will continue to provide core support for the digital and intelligent transformation of various industries, emerging as a crucial cornerstone for driving intelligent manufacturing and technological progress.